Saturday, June 11, 2011

One sign you?re at the top of a market rally is a rush by the latest chic sector to get their IPOs out while the getting is good.? A few weeks ago we had professional social networking site LinkedIn. Within a few months, we will likely see internet game maker Zynga (creator of Facebook sensations FarmVille and Mafia Wars) and Groupon, whom I?m sure every reader of this site recognizes by now, follow suit.

LinkedIn made headlines on its first day of trading by spiking from its IPO price of $45 a share, to $83 at the open, and all the way as high as $120 by mid-day.? Of course, it made fewer headlines by falling $10 below its break price within a few weeks. Groupon has already received an avalanche of bad press and analysis since it filed for its IPO.? Many people are already reminded of the ?irrational exuberance? of the 1990?s dot-com bubble.

As you can guess, I?m about to pile on.? I am not, however, primarily a stock analyst or accountant, and I can?t give you an insightful picture of Groupon?s cash flow or LinkedIn?s EBITDA as a guide as to where their stock prices are going to move.? Nothing I say here constitutes advice to buy or sell any asset of any kind.? I?m a pretty good computer programmer with a decent knowledge of computer science-related math and a little business experience.? What I?m going to discuss are the central arguments that some have made for the ?this time it?s different? case, and why I believe them to be incorrect.

Let?s me dispense with a few preliminary points before I move into the granddaddy argument being made by Web 2.0 groupies and the companies themselves.

1.? The technology is better and programmers are more efficient

I haunt the programmer-focused news site Hacker News quite a bit.? A few months ago, there was a thread on there debating whether we are in another tech bubble or not.? I weighed in on the affirmative side, and there was a lively debate stretching hundreds of comments.? One point one of the commenters made was that web technologies are much better now, and web development tools make programmers far more efficient and shorten the development cycle.

It?s undoubtedly true that web technologies are much better now than they were in the 90?s.? On the consumer side, bandwidth is much better and websites have moved beyond static documents to full-on user experiences, complete with video, audio, animation, and drag-and-drop.? For programmers, languages like Ruby and Python, with their web development frameworks like Ruby on Rails, are much easier to use than the previous generation of languages, and they allow even amateurs to (relatively) easily build up web applications quickly.

As someone who writes code, I appreciate that.? On the other hand, isn?t this really a net negative from a business perspective?? As anyone who?s taken a microeconomics course knows, as barriers to entry fall margins go closer to 0.? Indeed, we can see that this is precisely the case with internet businesses in recent times.? LinkedIn, for instance, revealed that it made around $240 million in revenue in 2010, with $15 million in net income, with about 100 million users.? So, each user generates $2.40 in marginal revenue and $0.15 in marginal profit.? Elsewhere, it has been reported that the average LinkedIn user spends roughly 30 minutes per month on the website.? That tell us LinkedIn needs to attract 50 million man-hours a month to sustain its current revenue.

I suspect you would see the same picture at similar companies such as Facebook.? It?s a problem for forward growth potential, but it?s also a problem for smaller companies trying to enter the internet space. Realistically, how many web applications are going to pull in 100 million registered users or generate 50 million man-hours of use per month?? That?s not to say every company needs the scale of LinkedIn to be considered successful, but for consumer web applications, we can begin to appreciate the problem these low margins are going to cause them.

2.? The dollars flowing into the internet sector are fewer than in the 90?s

This one is true, but the amount of venture capital, and now consumer capital, flowing into tech companies has occurred alongside similar massive run-ups in the prices of commodities and a few other sectors of the stock market.? The common denominator is loose fiscal and monetary policy.? This sort of ?me too? defense only works to demonstrate that the impact of the current internet bubble bursting will be smaller than the previous bust, not that there isn?t one happening.

Just look at the valuations of some internet companies on or before their IPO dates - LinkedIn: $9 billion, Zynga: $10 billion, Groupon: $9 billion, Twitter: $10 billion, Facebook: $60 billion (!!!).? Now, look at the 2010 profits of the two companies we?ve seen the books for - LinkedIn: $15 million, Groupon: -$434 million (!!! - yes that?s a negative sign).? Yes, these are only a ?few? companies, but they are emblematic of the bloated valuations being given to companies with no clear business models that are operating in markets with few barriers to entry.

That won?t end well.

And finally - 3. The ?network effect?

I?ll let Wikipedia lead off with a quick summary of what the ?network effect? is:

In economics and business, a network effect (also called network externality or demand-side economies of scale) is the effect that one user of a good or service has on the value of that product to other people. When network effect is present, the value of a product or service is dependent on the number of others using it.

The classic example is the telephone. The more people own telephones, the more valuable the telephone is to each owner. This creates a positive externality because a user may purchase a telephone without intending to create value for other users, but does so in any case. Online social networks work in the same way, with sites like Twitter and Facebook being more useful the more users join.

It?s easy to see why people apply this reasoning to internet businesses, especially social networks.? Heck, ?network? is even in the description of the site!? This analysis, however, is lazy.? Fundamentally, it ignores how the ?network effected? business generates its revenue.? Telephone companies make money because a telephone can only be used by patching into infrastructure that is difficult to build up to any useful scale without a large amount of investment.? In other words, the act of making the telephone call itself is valuable and can be charged for.? The network effect ?worked? in this case because more users meant there were more reasons to make telephone calls, exponentially more reasons in fact, and therefore more calls could be billed by the telephone providers.?

This is not how social networking sites like LinkedIn and Facebook make money.? Signing up for their websites is free.? Instead, these websites make money by selling advertising and sometimes premium subscription services like LinkedIn Recruiter (only $500 a month!).? More users does, of course, present more opportunities to generate revenues from advertisements, but this is fundamentally a linear progression rather than the exponential one the network effect predicts.? Analysts who get giddy over LinkedIn?s huge revenue growth from 2009 to 2010 are missing the point.? Let?s put it side by side to see what?s happening.

- 2009 users: ~40 million --- 2009 revenue: ~$120 million

- 2010 users: ~100 million --- 2010 revenue: ~$240 million

In other words, LinkedIn required 2.5x user growth to generate 2x revenue growth.? That?s pretty close to the linear progression I predicted above.? In fact, revenue growth fell behind user growth by a noticeable ratio.? What if these so-called network effect business are, in fact, logarithmic rather than exponential?? There are good mathematical reasons to believe this is the case.?

To see why, let?s briefly dive into a once-esoteric-but-now-quite-hip (depending on your definition of hip!) branch of mathematics called combinatorics.? I?ll again turn it over to Wikipedia to a brief explanation of what combinatorics is:

Combinatorics is a branch of mathematics concerning the study of finite or countable discrete structures. Aspects of combinatorics include counting the structures of a given kind and size (enumerative combinatorics), deciding when certain criteria can be met, and constructing and analyzing objects meeting the criteria (as in combinatorial designs and matroid theory), finding ?largest?, ?smallest?, or ?optimal? objects (extremal combinatorics and combinatorial optimization), and studying combinatorial structures arising in an algebraic context, or applying algebraic techniques to combinatorial problems (algebraic combinatorics).

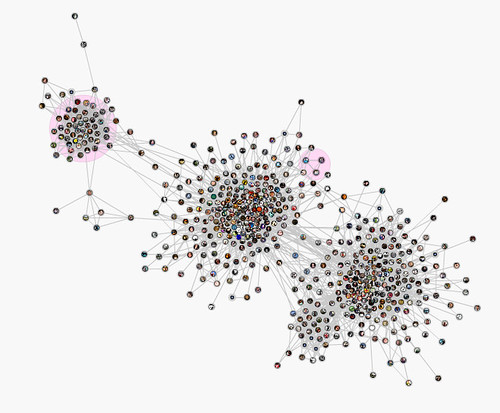

I can tell you?re all asleep already.? If it helps, there?s a branch of combinatorics that flies under the name of ?graph theory? or ?network theory?, and that is what we?re primarily interested in.? Here?s a picture to make things a little more concrete:

On the surface, that image looks almost incomprehensible, but it?s essentially a graphical representation made by a friendly geek that displays his social network on Facebook.? Each of the dots is a person, and each line between dots indicates those two dots are Facebook friends with each other.? In fact, this is a great image because it shows two graph theoretic phenomena that lead inescapably to the conclusion that we should expect the revenue growth of LinkedIn and Facebook to tail off, rather than multiply exponentially, as they add users.

The first phenomenon is small-worldness, which is essentially a state in which there are many clusters of nodes in a graph that are highly connected with each other and not very connected with any outside nodes.? In the above image, it?s easy to pick out three such clusters.? In the non-cyber world, this is of course how humans, who began history grouped in small tribes, relate socially.? We have a small group of core friends and companions who all know each other, with a few connections to other cliques here and there.? Online social networking is no different, as a cursory glance at your friends or connections lists would no doubt show.? Even those who have hundreds or thousands of friends on social networking sites only really communicate with a chosen few.

The second phenomenon the concept of graph diameter, which is the amount of paths that must be crossed to get between the two nodes that are determined to be the furthest apart from each other in the network.? In a graph characterized by small-worldness, the diameter of the network can be quite high, because a lot of effort is expended finding the few people in each clique who can bridge you to the next clique.? This is, again, how humans relate in real life.

So with the introduction out of the way, let?s turn back to Groupon.? Groupon?s network effect argument is predicated on the claim that as it signs up more consumers, more businesses will want to sign on to attract larger numbers of new customers, and more variety in the deals will in turn attract more consumers in a virtuous cycle.? Given what we know about network theory, it?s fairly easy to show this argument is on shaky ground.? The number of customers a deal can attract is limited by the number of customers within the business?s network, which in this case is usually limited by geographically.? Most customers won?t drive 25 miles, even for a 75% discount.?

Groupon can initially provide a benefit to the business by alerting more customers in its geographic network to its existence, but as Groupon signs on more and more customers, they eventually reach the point where their customer base for any given deal is saturated.? Since their revenue is based on how many customers take advantage of the deal, we would expect to see their revenue increase logarithmically and top out at a predictable number.

The same thing happens with ?true? social networking sites.? As I showed above, selling advertising is not a revenue model subject to the network effect, no matter who you are.? Instead, the claim made by social networking sites is that user growth will exponentially increase the opportunity for users to connect on business opportunities, or other similar activities the site can charge a fee for.? To give a more concrete example, LinkedIn?s basic proposition is that you need to be LinkedIn to connect with the people you want to sell to, and you can only see the information you need to see about those prospects if you pay LinkedIn a fee for it.

Again, it?s obvious to see how these claims will eventually fall prey to the mathematical reality of the nature of these sites? users.? There is an asymptote beyond which the value LinkedIn provides cannot grow further, because the diameter of their social graph will have gotten too wide and the cliques too deep, and revenue-generating users, who are already a small minority of the site?s total users, will fall away from the site.? That obviously implies an asymptote for their projected revenue growth as well.? Most importantly, that asymptote will occur before they are done adding users (mathematically speaking, when the average distance between cliques rises above the amount of effort users are willing to expend to navigate them).? This implies they will eventually enter a period where each additional user is actually a net zero, or even net negative, to marginal revenue.

Conclusion

What I hope I?ve been able to demonstrate is that the internet companies of today are still subject to the same physics they were in the late 90?s, and that most have business plans that are highly questionable.? That does not mean none will be successful - after all, the previous dot-com boom produced some true value providing companies such as Google and Amazon - but it means caution is warranted if you are considering spending money on social networking in your business or investing your own money in internet stocks.? Again, that?s not a recommendation to buy or sell any asset you may have; my goal was merely to provide a framework for reasoning about the current markets and the latest tech sector mania.

Posted by Aaron on 06/11/11 at 12:50 PM ? (0) Comments ? Print Vers. ? PermalinkPage 1 of 1 pages

Source: http://www.eternityroad.info/index.php/weblog/4943/

adam levine christina aguilera rasputin sherpa usta terrelle pryor college humor

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.